Missed Opportunity? Rethinking Quality of Life Analysis in the SONIA Trial

created by DALL·E

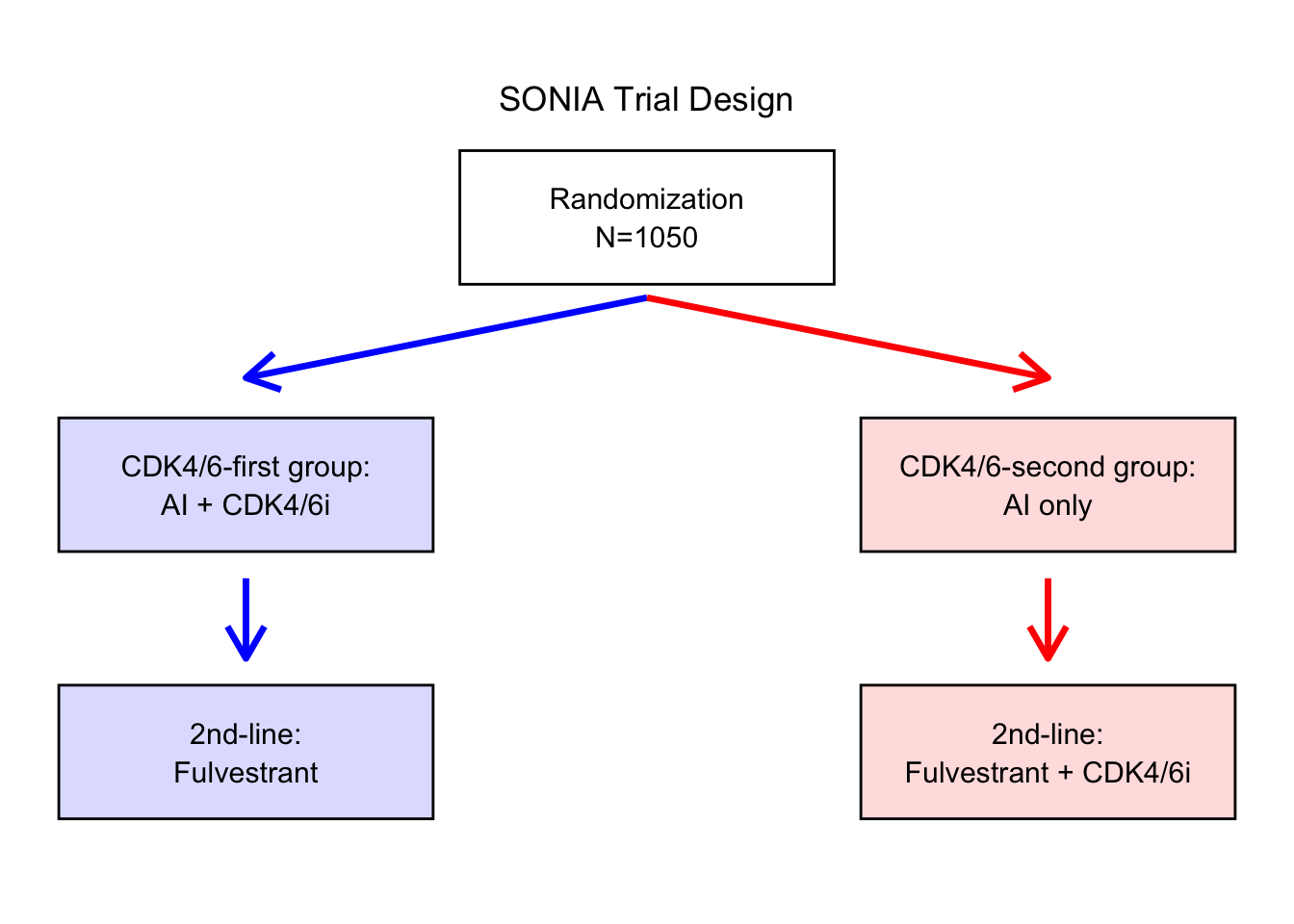

created by DALL·EThe SONIA trial shook up conventional thinking about advanced breast cancer treatment. For years, the standard approach was to start CDK4/6 inhibitors—powerful but costly and often toxic drugs—right away in HR+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer. SONIA tested that assumption.

In a large randomized trial, patients were assigned to either receive a CDK4/6 inhibitor up front (early group) or only after first-line hormonal therapy failed (delayed group). The results? No difference in overall survival. Delaying treatment didn’t worsen outcomes—and actually came with fewer side effects and lower costs.

But there’s one area where the results are … less satisfying.

The authors reported no difference in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) between the early and delayed treatment groups, based on the widely used FACT-B questionnaire. At first glance, this seems reassuring—patients felt just as good/bad either way.

But a closer look raises questions about what was being measured—and whether the tools used fully captured the patient experience.

The HRQOL Analysis Was Likely Too Simple

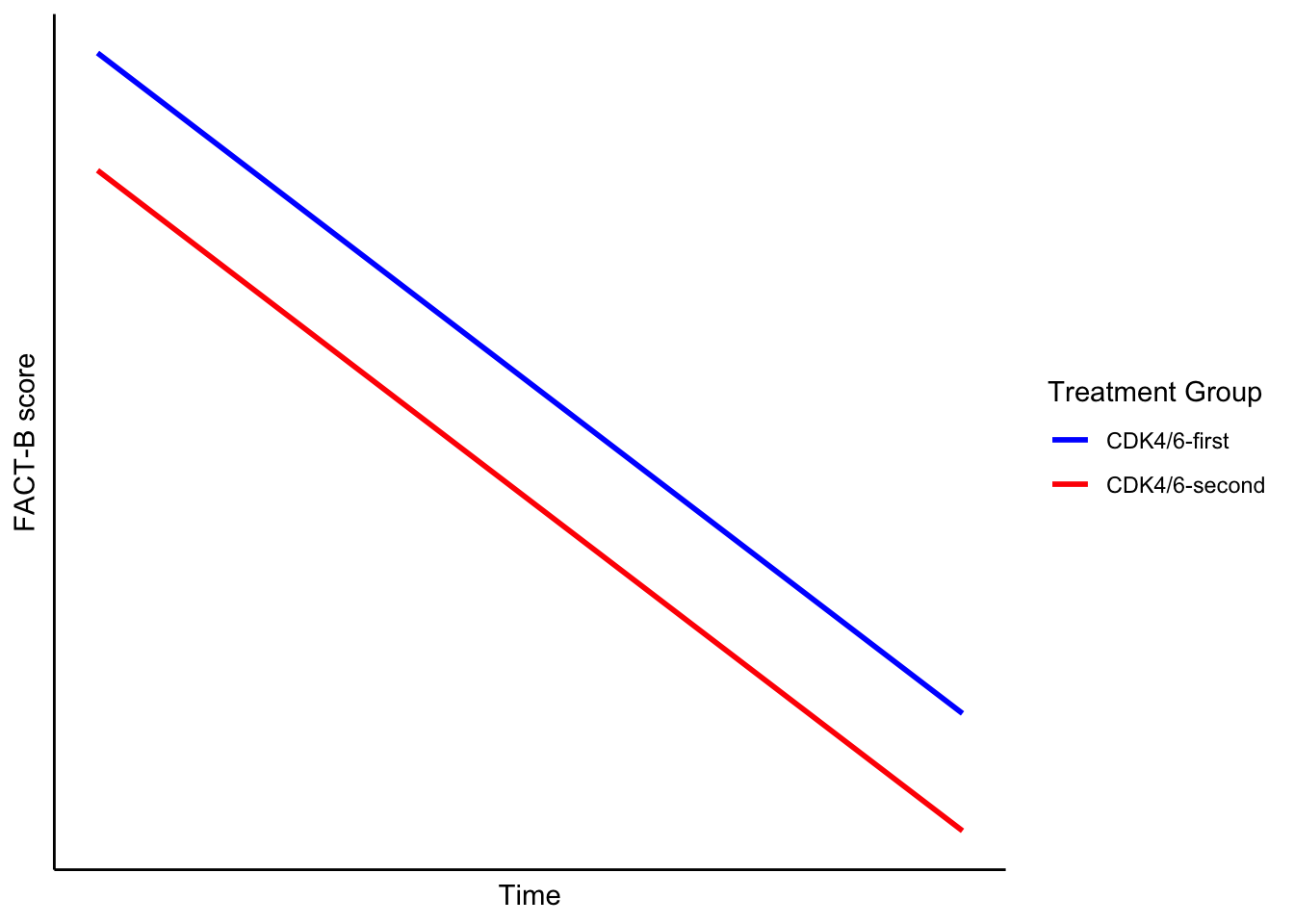

The authors used a main effects model to compare the FACT-B scores over time (see plot below). This approach makes two key assumptions:

- The only difference between the treatment groups is a constant shift—i.e., one group is consistently better or worse than the other across time.

- In their model, the coefficient for the “CDK4/6-second” group was −0.91, implying a minor, consistent shift.

- FACT-B scores change linearly over time.

Both assumptions are strong—and likely inadequate.

A Better Way to Ask the Question

Instead of asking, “Were average quality of life scores different across time?”, why not ask more patient-centered questions?

Hypothesis 1

Patients who start CDK4/6 inhibitors earlier (first-line group) experience a faster decline in quality of life compared to those who start them later.

Why might this be true? Because the first-line group had more severe side effects—more than 1,000 additional grade 3+ events than the second-line group. It’s logical to expect this would show up in their quality of life assessments.

Testing this hypothesis means including an interaction between time and treatment group. This would allow the slopes of the two groups’ HRQOL trajectories to differ.

Visually, this would look like one group’s line dropping faster than the other.

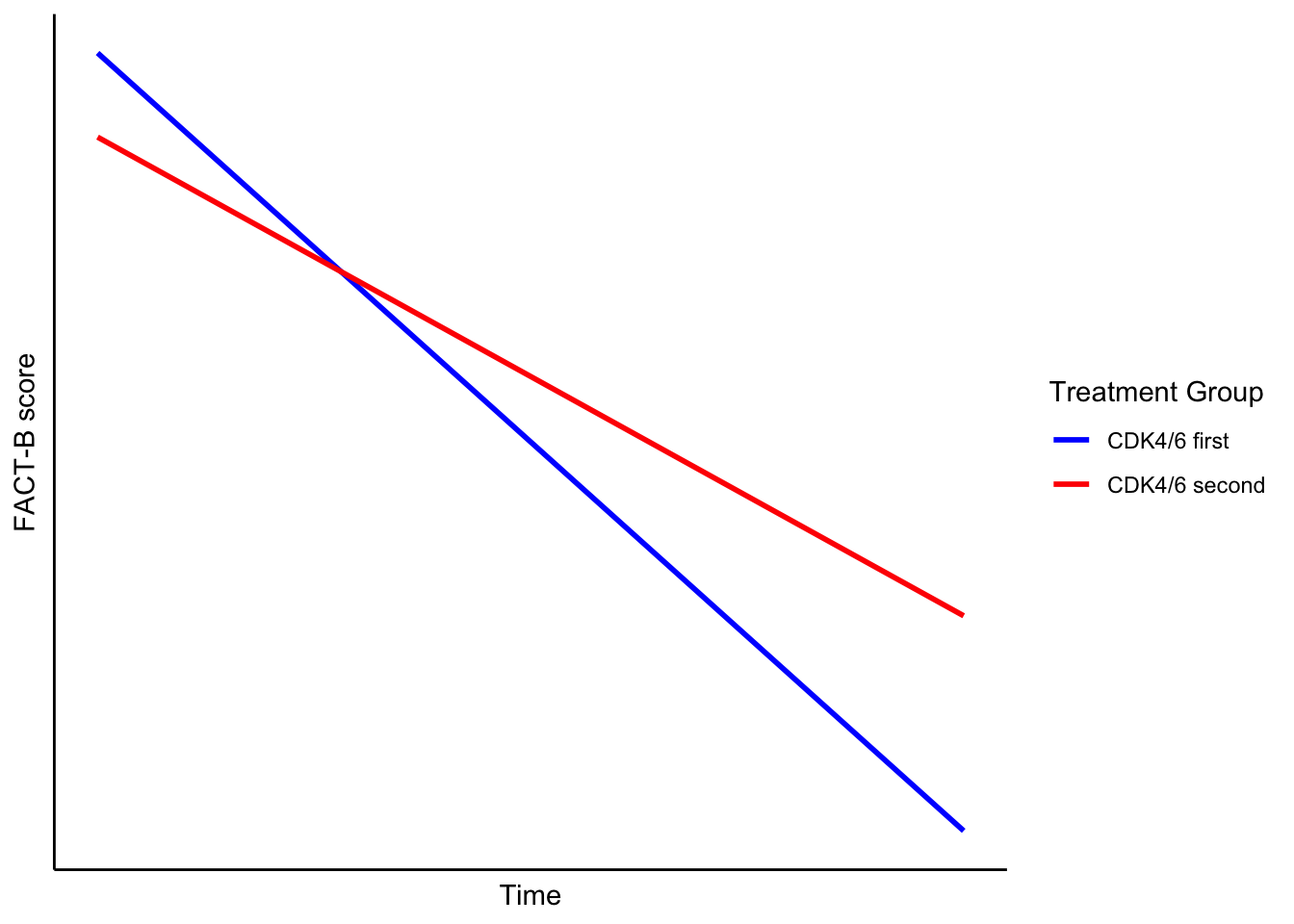

Hypothesis 2

The trajectories of the two groups may take different shapes—potentially non-linear—even if the final FACT-B scores are the same.

Here, I’m relaxing the idea that quality of life changes in a neat, straight line. Real life (and real cancer treatment) is rarely linear. Patients often experience early/late toxicity, and plateaus. A model assuming straight-line change might completely miss that.

Pictorially, this might show two lines crossing or diverging—even if they end at the same place.

Why This Matters

The SONIA trial is important, but its quality of life analysis could have gone further. With the right modeling, we might learn even more about how and when treatment side effects truly impact patients’ lives.

A more flexible, hypothesis-driven approach might have better captured what patients actually experienced.